Ten years in the making, In the Light of Reverence explores American culture’s relationship to nature in three places considered sacred by native peoples: the Colorado Plateau in the Southwest, Mount Shasta in California, and Devils Tower in Wyoming. Rich in minerals and timber and beloved by recreational users, these “holy lands” exert a spiritual gravity which pulls Native Americans into conflicts with mining companies, New Age practitioners, and rock climbers. Ironically, all sides see themselves as besieged. Their battles tell a new story of culture clashes in an ancient landscape.

Ten years in the making, In the Light of Reverence explores American culture’s relationship to nature in three places considered sacred by native peoples: the Colorado Plateau in the Southwest, Mount Shasta in California, and Devils Tower in Wyoming. Rich in minerals and timber and beloved by recreational users, these “holy lands” exert a spiritual gravity which pulls Native Americans into conflicts with mining companies, New Age practitioners, and rock climbers. Ironically, all sides see themselves as besieged. Their battles tell a new story of culture clashes in an ancient landscape.

In the Light of Reverence juxtaposes reflections of Hopi, Wintu and Lakota elders on the spiritual meaning of place with views of non-Indians who have their own ideas about how best to use the land. The film captures the spiritual yearning and materialistic frenzy of our time.

Our DVD (released in January 2003) includes seven additional scenes, an extended interview with Lakota scholar Vine Deloria, Jr., a new, 11-minute short film on Zuni Salt Lake and Quechan Indian Pass, and interviews with the filmmakers.

In the Light of Reverence is narrated by Peter Coyote and Tantoo Cardinal. The film premiered in San Francisco on Saturday, February 17, 2001 at the Palace of Fine Arts. It received the Best Documentary Feature Award at the American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco. It was nationally broadcast on the PBS series P.O.V. on August 14, 2001 and was seen by three million people.

Full Film https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_a0sdI5tCDYdTJMT3dUNHdKbkU/view?usp=sharing

The Three Stories

The Wintu and Mount Shasta

At 14,162 feet, rising from the surrounding forest, Mount Shasta dominates the landscape of northern California. In a meadow just below treeline, two communities gather for summer healing rituals amidst a carpet of wildflowers. New Age practitioners have gravitated to Panther Meadows for decades to pray, dance, sing and drum. It is a power spot, a special place that provides healing and peace. One group leader says he brings paying customers to Panther Meadows every year: “We’ve been camping here for a week, praying and healing ourselves. This is a sacred space.”

At 14,162 feet, rising from the surrounding forest, Mount Shasta dominates the landscape of northern California. In a meadow just below treeline, two communities gather for summer healing rituals amidst a carpet of wildflowers. New Age practitioners have gravitated to Panther Meadows for decades to pray, dance, sing and drum. It is a power spot, a special place that provides healing and peace. One group leader says he brings paying customers to Panther Meadows every year: “We’ve been camping here for a week, praying and healing ourselves. This is a sacred space.”

Northern California’s Wintu community also conducts a renewal ceremony in the meadow. Florence Jones feels that the New Age “ceremonies” offend the mountain. She is the 88-year-old top doctor of the Winnemem Wintu, and leads a thousand-year old ceremony at a spring in the meadow. Wintu religion focuses on healing and re-creating natural resources, including humans, plants, animals, the spring, and the mountain itself. Through a tobacco-induced trance, Mrs. Jones receives messages from the spring concerning community healing. She now passes her traditions on to the next generation, led by her forty year-old niece, Caleen Sisk-Franco. It disturbs them that “New Agers” dance naked in the meadow and leave crystals in the water. As they arrive for their ceremony they notice that the walls of the spring are collapsing due to people climbing in and out. Praying over the spring during the ceremony, Sisk-Franco breaks into tears: “There are a lot of other springs on this mountain. Why can’t those people go there?”

The Forest Service has proposed a multi-million dollar ski resort a few hundred yards away, with ski runs coming right down through Panther Meadows. We hear passionate arguments for the preservation of both culture and “sacred” American freedoms. Real estate agent and ski resort proponent Jim Ayer maintains: “It’s a religious battle, unfortunately. Our unalienable right is to have private property-that’s what our founding fathers based everything on. The pursuit of happiness is the pursuit of private property, and, now that’s being eroded, in essence, under the guise of religion.”

Mrs. Jones, Sisk-Franco, and several Wintu elders arrange a meeting with the Forest Service supervisor, Kathy Hammond, to discuss options for protecting Panther Meadows from the encroachment of a ski resort and the desecration of New Age practices. Mrs. Jones says to Hammond, “We have to get a permit from the Forest Service to come here, but you let every Tom, Dick and Harry put crystals in the water. They ruin my spring.” Hammond nods sympathetically, but says, “A lot of people are very unhappy with me, and I can’t give you special rights there without giving it to everyone. I’m trying to figure out a way for it to happen, but they’ll sue me because it’s public land.”

What ethics apply to outsiders who want to visit a Native American sacred site? To see a list of eight principles formulated by Sacred Sites International click here.

What considerations should guide journalists and educators when working with native communities? The Alaska Native Knowledge Network has created a set of Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge for authors, educators, publishers, photographers, filmmakers, illustrators, land managers, community organizers and the general public.

On February 19, 1998 U.S. Forest Service Supervisor Sharon Heywood decided against construction of a multi-million ski resort on Mount Shasta. Heywood cited Native American feelings for the mountain as one of the key factors in making her decision.

The Hopi and the Colorado Plateau

The biggest machine on earth rips coal from Black Mesa in Arizona. Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, Cultural Preservation Officer of the Hopi tribe, looks sadly as dust clouds the desert air. “We have 2,100 archaeological sites here that will be destroyed by mining,” he says. “We have failed our ancestors.” Kuwanwisiwma tells an old story of a covenant made by his ancestors with the powerful spirit-being Massau, in which the Hopi promised to take care of their homeland, to preserve its balance through prayer and ceremony, and to protect its most rare, life giving element-water. This covenant helped the Hopi survive in a harsh desert for a hundred generations, until they collided with materialism, industry and commercial values. Now, a web of Hopi sacred places across the Colorado Plateau is under siege. Sitting in front of a petroglyph panel, he says: “We consider archaeological sites to be shrines and living entities. This is where our ancestral people lived. When you disturb an archaeological site, in our Hopi view, you disturb a living entity.”

Kuwanwisiwma takes us to a Hopi sacred site near the Peabody Coal Company strip-mine, where precious desert springs are threatened by the pumping of 3 million gallons per day of drinking-quality underground water for a coal slurry line. For Peabody, slurrying coal is less expensive than trucking it to Nevada, where it feeds the Mohave power plant. Kuwanwisiwma explains the relationship between story, ceremony and water as central elements of the Hopis’ sense of the sacred. From the Hopi point-of-view, their culture and livelihood are being sacrificed for Peabody’s coal. But this is hardly a black-and-white story. The Hopi Tribal Council leased Black Mesa to Peabody in 1966 for $10 million per year, under duplicitous legal advice from John Boyden, a lawyer who was working for both Peabody and the Tribal Council. The council’s actions made land and water commodities that could be bought and sold. What are the Hopi’s religious and political interests? Today, Kuwanwisiwma argues that Boyden and Peabody were the culmination of a long parade of “outsiders on the payroll,” starting with explorers, ethnographers and photographers in the late 19th-century who systematically commodified Hopi ceremonial secrets and extracted the natural resources that Hopis have a covenant to protect.

Kuwanwisiwma takes us to a Hopi sacred site near the Peabody Coal Company strip-mine, where precious desert springs are threatened by the pumping of 3 million gallons per day of drinking-quality underground water for a coal slurry line. For Peabody, slurrying coal is less expensive than trucking it to Nevada, where it feeds the Mohave power plant. Kuwanwisiwma explains the relationship between story, ceremony and water as central elements of the Hopis’ sense of the sacred. From the Hopi point-of-view, their culture and livelihood are being sacrificed for Peabody’s coal. But this is hardly a black-and-white story. The Hopi Tribal Council leased Black Mesa to Peabody in 1966 for $10 million per year, under duplicitous legal advice from John Boyden, a lawyer who was working for both Peabody and the Tribal Council. The council’s actions made land and water commodities that could be bought and sold. What are the Hopi’s religious and political interests? Today, Kuwanwisiwma argues that Boyden and Peabody were the culmination of a long parade of “outsiders on the payroll,” starting with explorers, ethnographers and photographers in the late 19th-century who systematically commodified Hopi ceremonial secrets and extracted the natural resources that Hopis have a covenant to protect.

Today, Kuwanwisiwma is assuming the role of cultural bridge to the outside world that has long been performed by his uncle, Thomas Banyacya. For fifty years, Banyacya traveled the world to warn people of the dangers of upsetting the spiritual and ecological balance of the canyon country the Hopi have inhabited for thousands of years. Banyacya takes us to Grapevine Canyon, where he offers a prayer feather at a spring, to the Mohave power plant, where Peabody’s slurry line ends, and to an ancient kiva at Chaco Canyon, where he says a prayer for rain in a summer of drought. Banyacya passed away in February, 1999-he is now an ancestor.

Dalton Taylor makes a pilgrimage every year to plant prayer feathers at a series of shrines that ring the Hopi homeland. Taylor takes us to Woodruff Butte, where seven of these shrines have been destroyed by a gravel mining operation, and ancestral rock writing has been defaced by gunfire. We also visit the Grand Canyon, where Taylor consults with Park Service archeologist Jan Balsom about disruption of Hopi offerings by tourists. Balsom agrees to close off a trail to keep tourists away from the Hopi shrine-a clear example of the new level of sensitivity within the federal government regarding Native American sacred sites.

What recourse do Native Americans have to prevent intrusions on significant cultural sites or commodification of important imagery? In 1978 the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) was passed, a Congressional policy statement that mandated accommodation of native religious practices at sacred places. However, in a 1988 case known as the “GO Road,” the Supreme Court ruled that neither the first amendment nor AIRFA assured the rights of Indians to worship on public lands, if that worship interfered with a federal project that benefited more people. It was a devastating loss, and Native Americans’ Constitutional rights were further eroded.

The Hopi Cultural Preservation Office presents specific guidelines for how to respect Hopi religious practices. Their statement on “Intellectual Property Rights” explains the historical appropriation of ceremonial objects and rituals. “Respect for Hopi Knowledge” contrasts the Western idea of having a “right” to know something with the Hopi idea of restricting knowledge to those who have the wisdom to use it.

The Lakota and Devils Tower

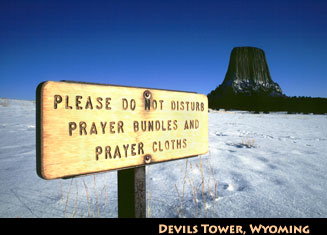

The current battleground in the legal conflict is in the northern Plains, at Mato Tipila, the Lodge of the Bear, also known as Devils Tower. At issue: climbing a sacred site.

Every June, Lakota youth run 500 miles around the Black Hills. We see runners approach Devils Tower and a sudden rainstorm tests their commitment. They pound on through the deluge. The sun emerges as they reach Devils Tower. Their clothes dry on tree branches in camp, as Lakota elder Johnson Holy Rock tells a story to the young runners: “If a man was starving, he was poor in spirit and in body, and he went into the Black Hills, the next spring he would come out, his life and body would be renewed. So, to our grandfathers, the Black Hills was the center of life, and those areas all around it were considered sacred, and were kept in the light of reverence.”

In a lush meadow beneath the tower, Oliver Red Cloud leads the runners in a pipe ceremony, praying and singing as dawn breaks. A red prayer bundle hangs in a pine tree near the towering monolith. The silence is broken by a hammer driving a piton into smooth brown rock. “Another day in paradise!” one man shouts to another. They gaze up the vertical slope of Devils Tower, one of the premier climbing challenges in the world, made famous by Steven Spielberg in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. For the Lakota, and other tribes of the northern plains who perform sun dances and vision quests nearby, solitude and silence are disturbed by the presence of rock climbers, whose culture dictates that the tower be used for personal adventure, not communal prayers. The National Park Service has tried to find common ground by proposing a compromise, asking climbers not to climb during the month of June, when Indian ceremonies are at their height. 85% of climbers have stopped climbing in June. However, several climbers in alliance with the conservative Mountain States Legal Foundation have sued the Park Service, claiming an inappropriate government entanglement with religion. (It is a federal offense to climb Mount Rushmore, considered by many to be a bona-fide American “sacred site.”) Many climbers see the Tower as their own sacred site, and feel that banning climbing violates their religious freedom. “We may be interfering with their prayers,” says Frank Sanders, “but it’s not fair for them to lock me out of my church altogether.”

In a lush meadow beneath the tower, Oliver Red Cloud leads the runners in a pipe ceremony, praying and singing as dawn breaks. A red prayer bundle hangs in a pine tree near the towering monolith. The silence is broken by a hammer driving a piton into smooth brown rock. “Another day in paradise!” one man shouts to another. They gaze up the vertical slope of Devils Tower, one of the premier climbing challenges in the world, made famous by Steven Spielberg in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. For the Lakota, and other tribes of the northern plains who perform sun dances and vision quests nearby, solitude and silence are disturbed by the presence of rock climbers, whose culture dictates that the tower be used for personal adventure, not communal prayers. The National Park Service has tried to find common ground by proposing a compromise, asking climbers not to climb during the month of June, when Indian ceremonies are at their height. 85% of climbers have stopped climbing in June. However, several climbers in alliance with the conservative Mountain States Legal Foundation have sued the Park Service, claiming an inappropriate government entanglement with religion. (It is a federal offense to climb Mount Rushmore, considered by many to be a bona-fide American “sacred site.”) Many climbers see the Tower as their own sacred site, and feel that banning climbing violates their religious freedom. “We may be interfering with their prayers,” says Frank Sanders, “but it’s not fair for them to lock me out of my church altogether.”

Lakota scholar Vine Deloria, Jr., an intellectual guide through this complex terrain, says, “It’s not that Indians should have exclusive rights at Devils Tower. It’s that that location is sacred enough so that it should have time of its own. And once it has had time of its own, then the people who know how to do ceremonies should come and minister to it. That’s so hard to get across to people.” Many Americans, not just Indians, recognize the natural world’s inherent spirit and vitality, and are working to protect it and provide for a new way of seeing the Earth and our relationship to it.

The significant questions this film documents and raises are being worked out at the grass-roots. Changes in public policy are occurring, driven by sympathetic government officials in the field. Native people and federal agents alike recognize the value of using public education, rather than the force of law, to legitimize native concerns over sacred site protection. At Devils Tower, Park Superintendent Deb Liggett says she has a mandate from the American people to preserve cultural properties. A federal judge agreed, though his decision has been appealed. At Mount Shasta, Forest Supervisor Sharon Heywood decided against the ski resort at Panther Meadows, due in part to the mountain’s spiritual significance to Native Americans. At the Grand Canyon, Jan Balsom, the National Park’s Chief Archaeologist, walks along the rim with Hopi elder Dalton Taylor. He tells her that tourists have been taking eagle feathers from an important shrine; she agrees to block the trail to keep tourists away. Taylor quietly nods and says, “Thank you. All we want is for the prayer feathers to be respected and not destroyed.”

The Issue

Freedom of religion is one of the fundamental values in American society. For indigenous communities such as the Wintu, Hopi and Lakota, the earth is sacred, and their religious practices hinge on their responsibility to take care of the natural world by performing ceremonies that are linked to specific places. However, the mainstream society’s value of religious freedom does not apply to this indigenous philosophy and the practices that have grown from it. Land-based religions were not in the minds of the founding fathers when they wrote the First Amendment, nor are they understood by the American public today. What is our society’s responsibility to Americans who have been forced off their homelands, politically and economically dispossessed, and even massacred for their beliefs? These acts seem unthinkable now, but the denial of religious freedom to land-based religions is a continuation of our nation’s old ways of dealing with the “Indian problem.”

Mining, logging, dams and other forms of economic development have a long and continuing history of destroying ceremonial sites. Today, rock climbers, New Age pilgrims, photographers, anthropologists and skiers present surprising new threats. Some members of these groups feel that native peoples’ efforts to protect sacred sites are a political ploy to regain control of lost lands. Determined government bureaucrats have taken the unusual position of supporting native people’s struggle to secure religious freedom. Fundamental to our story is a clash of world views: a utilitarian view of the earth as an economic resource, and a spiritual view of land as animated by ancestral spirits and mysterious forces that create cultures, traditions-and conflicts. As one native elder put it, “This is not a playground. This is sacred ground.”

This story’s implications are profound, not just for its constitutional consequences, but for the questions that confront America’s future as a multicultural society: can we accommodate such diverse cultures, histories, and philosophies into our educational system and our land-use policies? Must the “majority” (who do not practice land-based religions, but nevertheless have relationships with special places) sacrifice rights to use public lands or pursue happiness (through private property ownership) to protect “minority” religions? Will millennia-old philosophies be sacrificed for economic prosperity?

For many Americans, Indian and non-Indian, the Holy Land is here. We all want to protect certain places. Whether those special places are on public land or private property, how does our society decide how best to protect them and who may use them? While we debate, Native Americans are still losing ground-sacred ground.

Produced and Directed by Christopher McLeod. Co-Produced by Malinda Maynor. Written by Jessica Abbe. Edited by Will Parrinello.

Comments