This is your community page where members can post ... anything!

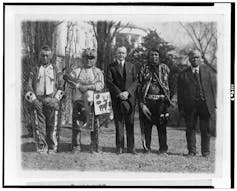

President Calvin Coolidge meeting with a delegation of Native Americans at the White House. Library of Congress

The US president, Donald Trump, spoke in June to a delegation of tribal leaders at the White House, claiming that: “Infringements on tribal sovereignty are deeply unfair to Native Americans and Native American communities.” His sincerity was hard to believe.

From his support of the Dakota Access Pipeline to his unabashed public appreciation for the mastermind of Indian Removal, Andrew Jackson, Trump has a long way to go before his platitudes become reality. Yet, this is not unique to Trump.

US presidents have an overwhelmingly poor track record when it comes to bettering the position of America’s First Peoples. Thomas Jefferson, the architect of American independence, treated Indian Country as an inconvenience during his terms in office. Abraham Lincoln, “the great emancipator”, allowed his generals to commit atrocities against Native American communities throughout the Civil War, leading to massacres at Sand Creek and Bear River.

Even when presidents have been sympathetic towards the plight of the American Indian, their actions have often proved contradictory. However, some have endeavoured to follow through on their statements and in light of Trump’s comments, several of them are worth highlighting.

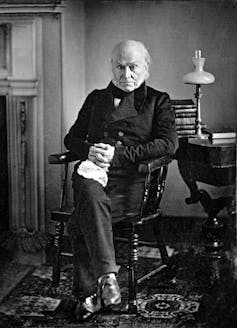

John Quincy Adams (1825-1829)

John Quincy Adams learnt first hand the difficulties of implementing fair Indian policy. Wikimedia Commons

John Quincy Adams learnt first hand the difficulties of implementing fair Indian policy. Wikimedia Commons

Adams, a former ambassador, secretary of state and son of a previous president himself, may have been the most qualified man to assume the nation’s highest office, yet lacked a cohesive Indian policy at the start of his term. While initially ambivalent, Adams took great interest in the Creek Indians of Georgia who were being pressured by the state’s governor, George Troup, to give up their lands.

After receiving a delegation of Creeks in the capital, Adams intervened and demanded that Troup give the Indians a fairer deal for their lands, leading to the 1826 Treaty of Washington. This treaty was agreed upon between Adams and Creek leaders in Washington DC, a stark departure from previous Native American treaties which were often one-sided.

Unfortunately, this was to be but a temporary victory for the Creeks. Troup quickly organised another treaty to take the rest of the Creek lands and, while Adams threatened federal intervention against Georgia, he backed down due to fears of this incident sparking a civil war.

While Adams was ineffective in halting the march towards the calamitous Indian Removal of the 1830s, he became a strong and active critic of US Indian affairs for the rest of his life.

Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929)

President Coolidge looked to reverse decades of government neglect towards Indian Country. Library of Congress

President Coolidge looked to reverse decades of government neglect towards Indian Country. Library of Congress

“Silent Cal” was to many an unassuming man, but his Indian policy marked a real watershed in government relations with Native America. Before Coolidge, Indian policy had become a low priority of presidential administrations since the Dawes Act of 1887. This act ended up stealing large tracts of land from Native communities and devastated generations of indigenous families. When assuming office, Coolidge looked to set in motion a reorganisation of federal Indian policy.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted US citizenship to every Native American, was the first step to restricting the effects of the Dawes Act. This act gave Native Americans a political voice, while also giving them a government safeguard against fraudulent land purchases. Later, during Coolidge’s presidency, the Interior Department’s Meriam Report was finally published, which concluded that the Dawes Act had been a failure.

“It is not surprising,” the report claimed, “to find low incomes: low standards of living, and poor health” among the Indians of the United States. The Meriam Report – and Coolidge’s public support for its findings – paved the way for an overhaul of Indian policy.

Coolidge’s Indian policy was not a complete success. His administration started the desecration of sacred Lakota Sioux lands with the construction of the Mount Rushmore monument and the Indian Citizenship Act was vague on tribal sovereignty. Yet Coolidge’s efforts proved an essential foundation for future policies that improved the Indians’ standing, particularly Franklin Roosevelt’s Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Richard Nixon (1969-1974)

Nixon, even after his underhand Vietnam policy and resigning in disgrace, still retains a glowing record among Native American communities. Against the backdrop of “Red Power” and student protest movements, Nixon assumed office at a time of great anger among Native communities. With this in mind, the policy that Nixon implemented was unique as it was designed to be long lasting and address the core of these grievances: the role of tribal sovereignty.

Nixon showed genuine compassion towards Native communities by returning the ill-gotten sacred lands of the Blue Lake to the Taos Puebloin 1970. When signing the bill, Nixon commented that the US was starting on “a new road which leads us to justice in the treatment of those who were the first Americans”, a statement that turned out not to be just an empty platitude. During Nixon’s time in office, he increased the annual funding of the Bureau of Indian Affairs by 214%, ensuring that the bulk of these funds were to be given to tribal governments to do with as they saw fit.

The president’s reforms culminated in one of the most important acts for Indian Country: the Indian Self-Determination and Self-Organization Act of 1975, which returned power to the tribes. This was an act his presidency did not survive to see come into law. Motivated by the activism that engulfed America in the early 1970s, Nixon’s Indian policy remains the model example of how a POTUS can make lasting benefits for Native America.

Adams, Coolidge and Nixon are all tied by their genuine conviction to improve the lives of America’s indigenous communities. While their successes varied, they each left a noticeable impact on US Indian policy. Considering President Trump’s dismissive approach to Indian rights and tribal sovereignty, there is little hope of him continuing this infrequent presidential tradition.

Comments