This is your community page where members can post ... anything!

In the fall of 1868, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer commenced a controversial military operation against the Cheyenne.

By Arnold Blumberg

The conclusion of the Civil War saw the painfully reunited nation resume its westward surge. Complicating that surge was the Indian question: how best to remove the Native American peoples from the paths of white expansion. The United States Army, imbued with impatient confidence after defeating the redoubtable Confederates, felt that the resolution of the Indian problem would be a swift and simple matter. That assessment would prove to be disastrously wrong, for both sides.

The postwar opening of massive new areas for settlement and the building of the transcontinental rail system required a sufficient number of soldiers. The main theater of operations in the West immediately after the Civil War was the area of the Great Plains. Situated west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, this swath of land stretched 500 miles east to west and 2,000 miles north to south, covering parts of Canada as well as the United States. Included in this vast territory were the areas of Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North and South Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming. It was the home to over 100,000 Native Americans (Blackfoot, Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and others), proud, warlike people who would not be removed from their tribal lands without a struggle.

At the end of the Civil War, Congress authorized a Regular Army of 57,000 men, well under the numbers needed to secure the revitalized settlement of the West. A number of factors complicated the Army’s task. First, a strong force had to be maintained on the border with Mexico to keep an eye on the French-sponsored regime of Emperor Maximilian. Second, one-third of the army had to be deployed in the southern states to ensure the Reconstruction program would be completed. This left fewer than 15,000 troops to combat and contain the Indians, a task made harder by the fact that many of the soldiers were tied down manning the 255 military posts scattered throughout the nation. The result was predictable. In the majority of large-scale operations against the Indians, the Army was able to bring to bear at most 1,500 to 3,500 fighters at a time.

Furthermore, the Army was hobbled with a poor appreciation of the tactics required to defeat the Native Americans. The high command was still rooted in the ways of conventional warfare practiced during the Civil War. Accustomed by that conflict to rely upon weight of numbers and armaments accompanying ponderous advances, the Army leadership after 1865 needed time to relearn the lessons of fighting a frontier war in which it had not been actively engaged for almost 10 years. Meanwhile, it had to cope with a skilled foe whose use of deception, mobility, and guerrilla-style fighting techniques to avoid battle and strike unexpected blows was exceptional.

Hancock’s War

In 1866 an explosion of violence occurred in the Wyoming and Montana territories of the northern plains. The violence escalated with a bloody and unimaginable defeat sustained by the Army. On December 12, Captain William J. Fetterman, in command of an 81-man mixed infantry and cavalry detachment, was ambushed by 1,000 Indian fighters outside Fort Phil Kearny, Wyoming. Fetterman and his entire command were wiped out. At the time, the Fetterman Massacre was the worst defeat ever sustained by the American military on the Great Plains. Public anger over the event brought demands for the government to come down hard on the Native Americans. The Army was more than willing to do so.

From his headquarters in St. Louis, Lt. Gen. William T. Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, contacted Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, who headed the Department of Missouri, a geographical command encompassing Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Sherman ordered a military strike to teach the Indians a lasting lesson. In March 1867, Hancock gathered 1,400 infantry and cavalry, along with one artillery battery, and set out for Fort Larned, Kansas, to confront the Cheyenne and Sioux tribesmen camped at Pawnee Fork, 35 miles south of the fort.

During Hancock’s approach to the Indian village between April 12 and 15, the Indians fled their camp. Cavalry was sent after the escapees, but the only things they found were burned stage stations, run-off livestock, and butchered white civilians. In retaliation, Hancock set fire to the Indian camp on Pawnee Fork. What became known as Hancock’s War had begun.

The Medicine Lodge Treaties

For the next three months, the Army carried out fruitless searches for the Indian bands that repeatedly attacked and destroyed mail stations, stagecoaches, wagon trains and railroad workers along the Platte, Smokey Hill, and Arkansas Rivers. By the end of July, the Great Plains was embroiled in warfare. Except for a few abortive mounted expeditions, Hancock’s forces spent the summer strictly on the defensive. His 5,000 soldiers (chiefly infantry) were tied down defending a 2,500-mile perimeter made up of isolated military posts designed to protect the major travel arteries. Within this cordon ranged the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne, who took every opportunity to strike selected targets.

In July, the U.S. Congress negotiated a peace with all the warring tribes on the Great Plains. Embedded in the resultant treaty was the requirement that all the Indians be cleared from the area between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers and resettled to the north and south. Army brass reluctantly went along with the congressional peace initiative, mainly as a way of diverting attention from the clumsy and embarrassing campaign that Hancock had conducted.

Captain Louis M. Hamilton

The Medicine Lodge Treaties (the talks took place at Medicine Lodge Creek in southern Kansas) were finalized in October 1867 between the United States and the Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. The Native American signatories were consigned to a reservation in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). The peace created at Medicine Lodge Creek did not last long. Comprehending belatedly what they had bartered away and increasingly angered by the failure of the U.S. government to provide long-promised supplies, the Cheyenne and their traditional allies the Arapaho went on a rampage starting in July 1868. Aimed first at their longtime rivals, the Pawnee, the rebellious Indians also attacked whites along the Solomon and Saline Rivers.

In the Department of the Missouri alone, 110 white civilians were killed, 13 women raped, and more than 1,000 livestock stolen. In addition, uncounted farmhouses, wagon trains, and stage- coaches were destroyed. Numerous small-scale skirmishes occurred between soldiers and Indians, but the Army never succeeded in bringing the raiders to bay. Frustrated commanders vowed to pursue and kill any Indians who refused to move onto Medicine Creek Treaty lands.

Who was to Blame for the Treaty Violations?

In March 1868, Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan replaced Hancock as head of the Department of Missouri. The flinty-eyed Sheridan, diminutive and blasphemous, had successfully commanded a field army in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, as well as the Cavalry Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac, during the Civil War. Like Sherman, Sheridan believed in the concept of total war. To both men, total war meant subjecting the entire enemy population to the horrors of war, thereby undermining their will to resist. It had worked against the South—perhaps it would work against the Indians as well.

Although Sherman and Sheridan blamed Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders for instigating the recent disturbances, the facts were otherwise. Before the summer warfare erupted, the Cheyenne and Arapaho had moved south to Indian Territory to get away from the growing disorder north of the Kansas line. Most of the trouble was caused by young Indian men who resisted tribal authority and sought to plunder white settlers and their property. Others were members of the warrior society known as Dog Soldiers, who lived only to fight the white man and other hereditary enemies. The Army failed to separate the perpetrators of the summer violence from other tribal members who advocated peace with the whites.

One such peace proponent was Cheyenne chief Black Kettle. Born in 1801 near the Black Hills, Black Kettle was a longtime advocate of compromise with the United States. He sought to accommodate the Americans by signing several peace treaties with them in the hope of retaining some autonomy for his people. Despite his efforts, he and his tribe were attacked on November 29, 1864, at the Sand Creek Reservation in the Colorado Territory by territorial militia under Colonel John M. Chivington. The surprise assault on the Indian camp claimed 163 Cheyenne dead, mostly women and children. Black Kettle barely escaped with his life.

Even after the Sand Creek Massacre, Black Kettle continued to work for peace with the American government, but his standing with his own people never recovered from the debacle of Sand Creek. His acquiescence to later treaties caused many other Cheyenne to lose faith in his judgment and ability to lead them. This increased the influence of the Dog Soldiers, who insisted that war was the only answer to the growing white threat. To Sherman and Sheridan, Black Kettle’s inability to control his people was seen as an encouragement to further violence. The generals determined to eradicate the problem by severely punishing Black Kettle and his compatriots.

A Winter Campaign

Past experience showed that little success could be gained during the warm seasons when the Indians were free to move around the country. Sheridan reasoned that a radically different approach had to be tried—a winter campaign would be initiated. That was when the Indians were at their most vulnerable, unable to travel due to the heavy snowfall and forced to stay in one place for an extended period of time. Active operations during the winter by the Army, rarely seen before on the Great Plains, would yield the advantage of tactical surprise.

To shield white settlements and screen the concentration of his forces for the forthcoming campaign, Sheridan kept roving columns in the field throughout the month of October. The forces were to act as “beaters” to drive the Indians south of the Arkansas River and east toward the Antelope Hills. Sheridan’s main component, the 7th U.S. and 19th Kansas Cavalry Regiments, was to proceed to a point near the junction of Beaver and the North Canadian Rivers in Indian Territory and hit the Indians’ winter quarters along the headwaters of the Washita River. According to Sheridan, the objective of the mission was to “strike the Indians a hard blow and force them on to the reservations set a part for them, and if this could not be accomplished to show to the Indian that the winter season would not give him rest, and that he and his villages and stock could be destroyed.”

The 7th Cavalry was buoyed by the return of its former leader, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. Custer, a 29-year-old West Point graduate, class of 1861, had enjoyed a meteoric rise during the Civil War, going from a second lieutenant in 1861 to brevet major general of cavalry by war’s end. He had headed the 7th Cavalry during Hancock’s abortive campaign of 1866, but his performance then had been lackluster for so renowned a horse soldier. Unable to find—let alone bring to bay—the Indians during the campaign, Custer had been suspended from active duty and court-martialed for leaving his post to visit his wife. But Sheridan, who had commanded the young Buckeye during the Civil War, asked President Ulysses S. Grant to reinstate Custer to active command. The newly rehabilitated officer joined his regiment on October 11, 1868, two days after Sheridan received final authority to commence his winter campaign.

The surprise attack, 27 November 1868, on Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village on the Washita River, Oklahoma, by the 7th U.S. Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer.

Sheridan hoped to begin operations by the end of October with a movement to the Washita Mountains in the southwestern part of Indian Territory. The initial moves were designed to keep harassing the enemy during the winter until the Army could concentrate its resources for a major blow in the early spring. But the transfer of troops south was halted as a result of the inability to gather enough supplies at Fort Dodge, Kansas, to support the maneuver. As October wore on and the logistical base at Fort Dodge grew, other units of Sheridan’s command frequently but inconclusively skirmished with Cheyenne and Arapaho forces.

“Conflict of Rank”

On November 12, Colonel Alfred Sully led his command from their encampment just south of Fort Dodge. The column forded the Arkansas River and reached the Cimarron River on the 15th. By the 18th they had marched 110 miles south from the Arkansas, where they began constructing a supply base, rather unimaginatively dubbed Camp Supply, south of the North Canadian River.

As the men labored to build Camp Supply, Sully and Custer fought over who was entitled to command the expedition. Sully sought to exert command by reason of his Regular Army brevet rank of brigadier general. Custer countered by claiming his brevet rank of major general of volunteers trumped Sully’s argument. The dispute went unresolved, with Sully retaining overall command, until Sheridan joined them on November 21. Sheridan immediately settled the “conflict of rank” issue by packing Sully off north to Fort Harker, leaving Custer in command of the expedition.

The 7th Cavalry

The 7th Cavalry moved out from Camp Supply on November 23. They had hoped to be joined by the 19th Kansas by that time. But Samuel J. Crawford’s troopers would not reach Camp Supply until December 1, after a harrowing 20-day march through snow-covered ravines and gullies, beset by severe winter conditions and near starvation. As a result, the success of the operation would have to rely on the 7th Cavalry.

The 7th United States Cavalry had been created in 1866. Many of its officers were veterans of the Civil War, including company commanders Captains Frederick W. Benteen, Louis M. Hamilton, Robert M. West, and Thomas B. Weir. The unit also contained a goodly portion of combat veterans, as well as recent enlistees from all walks of life. Custer’s second in command was Major Joel Elliott, an Indiana native who had risen through the ranks during the Civil War to gain an officer’s commission. Elliott was a veteran of the Battles of Shiloh, Perryville, Corinth, and Stones River. He had transferred to the cavalry and participated in Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson’s famous Mississippi raid. By war’s end, Elliott had received two wounds as well as two brevet promotions. After mustering out of the Army in 1866, he sat for an exam that gained him a major’s commission in the 7th Cavalry. As the senior regimental major, Elliott had commanded the 7th in Kansas prior to Custer’s return in 1868. Custer considered him “a young officer of great courage and enterprise.”

Snow lay a foot deep on the ground when the 7th Cavalry moved out on November 23 in column of fours. Their mission was to track down a Cheyenne and Arapaho band that Custer had heard was moving north five days before. The soldiers’ route would cover 250 miles, south to the South Canadian River, then down to Fort Cobb, next southwest toward the Washita (or Wichita) Mountains, then northwest back to Camp Supply. The men carried 30 days’ rations with them. Custer led the way, compass in hand, as the troopers and 37 heavily laden supply wagons tramped their way south. On the 25th, after crossing numerous thinly frozen deep streams, the men spotted the Antelope Hills. By then the horses were greatly fatigued as a result of the hard going and difficulty of finding grass for them to eat on the snow-covered landscape.

Movement became even harder as the cold increased and a thick fog appeared. According to one participant, “it was necessary to dismount very often, and walk in order to prevent our feet from freezing.” That same day, Elliott was sent out on reconnaissance below the South Canadian River. He reported back that he had discovered a trail used by as many as 150 Indian warriors. He continued his reconnaissance until he stopped near a tributary of the Washita River to await orders from Custer.

Surrounding Black Kettle’s Village

After hearing of Elliott’s find, Custer determined to leave a small detachment with the wagons and take the rest of his men southeast across country to link up with Elliott and strike what he was sure were Indian villages on the Washita River, a tributary of the Red River that flowed just southeast of the South Canadian. The 7th crossed the South Canadian River into terrain characterized by rolling hills and undulating plains interspersed with wooded creeks and low-lying streams and valleys.

Custer had been right about the supposed location of the Indians. Since early November, about 6,000 of them occupied various villages along the Washita River, known to the Indians as Lodge Pole River. Abundant winter grass for their ponies as well as timber, drinking water, and firewood made the area a perfect resting place during the winter season. Across a bend at a point where the Washita ran roughly east to west, and south of the river between two gently rising ridges about two miles apart, stood the teepees of Chief Black Kettle. At this point the Washita was between nine and 12 feet wide and formed a crescent-shaped bend encompassing 30 acres, where most of the 51 lodges sheltering 250 people were situated. A mile to the west, large herds of Cheyenne ponies were turned out to graze. Black Kettle’s village was four miles west of the principal concentration of Cheyenne lodges. Arapaho and Kiowa camps were nearby.

Returning Indian raiders (the ones whose trail had been spotted earlier by Elliott) advised Black Kettle that they had seen a path in the snow made by enemy horses heading for the Washita encampments. The old chief discounted their story; he did not believe that white soldiers would be operating that far south in such wintry conditions.While the Indians debated the idea of an enemy advance, Custer and his men were approaching the Washita valley from the northwest. They first saw the Indian pony herds, and finally through the predrawn light Army scouts discerned the Cheyenne lodges, even entering the village before reporting back to Custer, who was waiting on a hillside a mile north of the camp. The scouts estimated the warrior strength in the village at only 150 men. After countermarching away from the village so that his presence would not be discovered by the Indians, Custer and his officers formulated their attack plan.

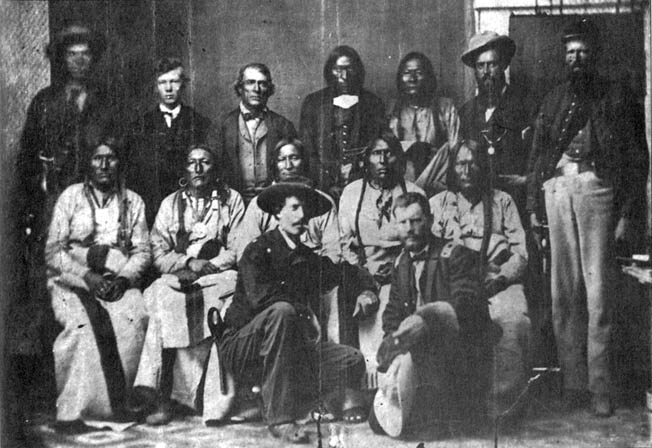

MEDICINE LODGE TREATY. The 1867 peace council at Medicine Lodge Creek, Kansas, between the U.S. military and the Kiowa, Apache, Comanche, and Cheyenne, which arranged for land on which to build the Kansas branch of the Pacific railroad. Contemporary wood engraving.

Custer decided to strike at daybreak. During the remaining hours of darkness, Custer split his command to surround the village and assault it from all sides. Elliott’s force (Companies G, H, and M) moved to the rear of the Indian position; Captain William Thompson with Companies B and F crossed to the south bank of the Washita and positioned themselves to the south. The west side of the village would be hit by E and I Companies under Captain Edward Myers after he crossed the stream. Companies A, C, D, and K as well as the regimental sharpshooter detachment under the command of Captain Louis M. Hamilton and accompanied by Custer were stationed on a ridge a mile northwest of the village. The attack was to be made simultaneously by all forces at dawn, but if any of the columns were discovered beforehand, they were to engage at once. The signal for the assault would be given by the regimental band.

“Killed Without Mercy”

By dawn, Elliott’s force was within three-fourths of a mile of the village, straddling both sides of the Washita, with most of the men dismounted and in skirmish order. To their left, Thompson’s command eased into place. On the ridge beyond, Hamilton’s troopers waited in the cold darkness standing by their horses, prohibited for obvious reasons from lighting fires.

As daylight drew near, the soldiers with Custer on the ridge were ordered to mount up. The men formed a single line, while the sharpshooters arranged themselves on foot in skirmish order in front of the left wing. Custer’s column crested a second ridge and saw what looked like a deserted village. Company K, on the right of the advancing line, was ordered to charge anyway and secure any Indian ponies encountered. As the troopers neared the Indian lodges scattered beyond the thick timber along the Washita, Custer turned to the regimental band leader and ordered him to strike up the regiment’s famous marching song, “Garry Owen.”

Before the first musical notes faded in the cold morning air, the soldiers rushed into the Indian camp. The dismounted sharpshooters veered away to allow their mounted compatriots a clear path over the river and up the steep banks. Indians came scrambling out of their tents, mostly unarmed and bewildered. Leading the attack aboard a black stallion, Custer fired his revolver at one Indian and rode over another before taking a position on a rise a quarter of a mile south of the stream. Hamilton’s men entered the encampment firing their pistols at any target that moved. Soon after, Hamilton was shot dead from his saddle.

From the west and south Myers’s and Thompson’s men stormed into the village, but the latter’s force failed to close the circle around the Indians, allowing many to escape to the east. Meanwhile, hemmed in from all directions, other Indians ran for the river, jumped into the freezing waist-high water, and fired at the enemy over the steep bank. Others fled downriver or sought protection behind trees and in ravines. Seeing the chaos around them, Black Kettle and his wife mounted a horse and raced into the river, but both were struck by bullets and fell mortally wounded into the Washita.

Within minutes the soldiers controlled the village. In the ear-rattling confusion, troopers chased and, according to one army scout, “killed without mercy” any Indian man, woman, or child within their reach. That was not completely accurate. Dozens were rounded up and taken prisoner on the slopes below the village.

The Building Indian Resistance

After the village was cleared and the prisoners rounded up, the real fighting commenced. Taking refuge in the timber near the Washita, isolated groups of Indians fought off the pursuing soldiers. Custer’s men dismounted and fought on foot, aided by the sharpshooters who effectively silenced the stubborn pockets of resistance in the ravines and along the river bank. At the same time, Custer sent his men to gather the women and children still in their teepees and to assure them that they would not be harmed.

As the village fell, 1st Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey and 20 troopers sought to capture the Indian ponies feeding nearby. After rounding up a herd of horses south and east of the village, he left to run down a group of Indians seen fleeing across the river to the east. After going three miles, the junior officer spied another large number of lodges along the Washita. Even worse, he also saw hundreds of Indian warriors coming after him. Placing his small detachment in skirmish order, Godfrey deftly leapfrogged his men over a number of ridges away from the rapidly approaching enemy. After a time, for some unexplained reason they faded from his front.

As Godfrey and his men withdrew, they heard heavy firing coming from the nearby south bank of the Washita, but the trees prevented them from discerning what was happening on the far shore. Reaching Custer, Godfrey reported his encounter with the new band of warriors and the presence of a large village downstream. Custer seemed surprised at their existence. Godfrey suggested that Elliott might be under attack. “I hardly think so,” said Custer, “as Captain Myers has been fighting down there all morning and probably would have reported it.”

What Godfrey had heard but not seen was the destruction of a small force of horse soldiers under Elliott, which was the reason why the Indians had stopped chasing him. During the assault on Black Kettle’s camp, Elliott had seen a group of hostiles slip through the gap between his and Thompson’s line. Gathering 18 troopers, along with Sgt. Maj. Walter Kennedy, Elliot gave chase. “Here goes for a brevet or a coffin,” Elliott shouted as he galloped off in pursuit of the Indians.

Upon reaching a point 21/2 miles east of Black Kettle’s village on the south bank of the Washita, Elliott was suddenly attacked by hundreds of Indians from several directions. Dismounting and taking cover in the tall grass, the regulars were showered with Indian bullets and arrows and killed to a man. Their bodies were gruesomely butchered and scalped. Soon after the massacre, newly arrived Indians from the east and north came within sight of Black Kettle’s camp.

Custer’s Surprise Withdrawal

A short time later Custer’s ammunition train arrived, having ridden through the loose cordon of Indians beginning to surround Custer’s position. The colonel sent out a skirmish line to engage the rapidly congregating Indians. While the two sides exchanged shots with each other, Custer ordered the village burned to the ground. He also sent companies under Benteen, Weir, and Myers to engage the enemy. After a few spirited charges, the Indians fell back.

As the fighting died down to the north, Custer instructed Myers to locate Elliott and his detachment. After riding two miles eastward down the river, Myers returned and reported his failure to locate the missing officer and his men. Custer did not renew his efforts to discover Elliott’s whereabouts. He was more concerned about the growing number of armed Indians in the area, and he feared that they might discover and attack his wagon train, then advancing from the South Canadian River and guarded only by 81 infantrymen.

The 1867 peace council at Medicine Lodge Creek, Kansas, ended Hancock’s War and consigned Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, and Cheyenne tribesmen to reservations in Indian Territory. It did not last long.

Late in the day, Custer determined to extract his command from a steadily worsening situation. After slaughtering more than 800 Indian ponies, Custer’s column, with wounded soldiers and 53 captured Indian women and children in tow, headed east along the north bank of the Washita toward the remaining Indian camps. Custer explained later that the enemy would never expect a movement in that direction and that the surprise would aid his withdrawal. He was right. Some skirmishing occurred between the soldiers and the pursuing Indians; but most of the warriors dispersed and headed for their lodges in order to protect their own families and property. The retreating soldiers, unmolested, were able to join their wagon train, and by late evening of the 28th crossed to the north of the South Canadian River to safety. Four days later they reached Camp Supply.

The Dawn of Total War in the West

That night, while the regiment’s Osage scouts held a “hideous scalp dance” in honor of the victory, Custer described the battle to Sheridan. The general, always to the point, wanted to know what had happened to Major Elliott. Custer, somewhat lamely, suggested that Elliott had simply gotten lost and would turn up eventually. It was “a very unsatisfactory view of the matter,” Sheridan replied, but conceded that it was “altogether too late to make any search for him.” From that time on, Custer never again enjoyed his commanding general’s full confidence.

Elliott’s loss notwithstanding, the Battle of the Washita was a ringing affirmation of Sheridan’s overall strategy of total war. At the loss of two officers and 19 enlisted men killed and another 11 wounded, Custer’s regiment had killed 103 Indian warriors. More importantly, the destruction of the Indians’ ponies, lodgings and food, combined with the brutal reality that the soldiers could strike them during any season of the year, was completely demoralizing. The war on the southern Great Plains would continue until June 1869, but it paved the way for the final triumph over the Indians in that theater. It also cast Custer in the public mind as the most important Indian fighter in the country, even though it proved to be his only major battlefield success against Native American forces. Seven and a half years later, at the Little Bighorn River in southern Montana, he would attempt another surprise assault on an Indian encampment—with vastly different results.

Comments